In the February 2012 issue of the Internet-based Eco-villages newsletter, Diana Leafe Christian, the editor, published a piece called “Systemic Consensus – Fast, Visual and Hard to Deal With”. In it, she described the development of an extension of consensus decision-making called Systematic Consensus. Diana praised many of its features, based on real experience that she has had with it.

Systematic Consensus has two main features. First, it allows participants in a decision-making group to express their degree of support for the options being considered. They use a scale – typically a scale running from 0 to 10 – 0 meaning no support, 10 indicating full support. They indicate their degree of support for each option on this shared scale. As a result, individuals can move beyond simple binary decision making – support or do not support. They can express nuances – degrees of support – that are far more thoughtful, and revealing, than simple binary choices.

Systematic Consensus’s second main feature is the collation and public posting of each individual’s level of support for each option on a group flip chart, poster or white board. The facilitator leads this process. As she or he does so, dynamically, in front of the group, the facilitator is creating a real time group profile that displays the range of support for the various options under consideration. As a result, the dialogue in the group is enhanced, leading to more productive outcomes.

Dinah goes on to explain how all of this works. She provides some concrete examples drawn from real involvement with a number of community groups. She demonstrates that is not simply a mechanical process, but one that requires real process leadership skill on the part of the facilitator. It’s a fascinating article. I recommend that you have a look at it. It’s available at the following URL – http://www.ecovillagenewsletter.org/wiki/index.php/Systemic_Consensus_%E2%80%94_Fast,_Visual,_and_Hard_to_Argue_With.

As I read it, I was reminded of the power of, and difficulty inherent in, facilitating productive consensus in groups. I remembered some of the difficulties that I had experienced when facilitating a group dedicated to achieve consensus early in my facilitator life. I learned through hard experience that great consensus building sessions make deep contributions to building a highly functioning team or a strong sense of community among individuals. But I also learned that skillful individuals can block or sabotage consensus in groups, bending other members to their own point of view through sheer self-centered determination. Achieving productive consensus is not always easy.

The two core concepts that underlie systematic consensus are important ones. They address some of the problems that can occur in consensus seeking groups. But these ideas are not new. They are a great contribution to the dialogue about the dynamics needed to build intentional communities. I have been working with very similar processes for years when facilitating problem solving groups in more conventional environments, both community and business. Some I developed myself. Others entered my facilitation took kit as a result of mentoring and coaching from facilitators who has struggled with the difficulties inherent in facilitating consensus long before I start to do so.

I hope that you will go take a look at Diana’s article. It provides background for following insights about facilitating group decision making and consensus.

Building Dynamic Group Profiles in Real Time

I have been using the visual charting technique in working with groups for several decades. Hedley Dimock[1], one time Director of the Centre For Human Relations and Community Studies, first introduced me to the idea of visually developing group profiles in front of a group. Since those days, I have learned that there are a couple of critical things to do when a facilitator chooses to use this technique.

- First, I get individuals to make a personal decision about where they stand on the issue or the options under consideration. I direct them to move into a “personal” space while they are doing so. As a result, they experience a physical separation between the space they are working in as a group and the place in which they make these personal decisions. This physical separation aligns with the cognitive distance that I want them to experience.

Often this is as simple as getting them to move around the room in some way that results in them being in different physical location from where they would be when the group is in its normal “working in group” configuration.

- I ask them to record their decision in some way, often by requesting that they do something as simple as writing down their stand on each option – e.g. simply recording the relevant number of the scale if we are using one. I always ask them to label this recording with their name. If multiple options are on the table, they record where they stand on each one in a way that clearly identifies each of the options.

I have found that this “personal recording step” is crucial in avoiding “group think”. Without it, people often change their “judgments on the fly” as they see the pattern of individual results being recorded on the publicly visual group profile. For some people, “belonging” is far more important than taking a personal stand. They “conform” to group patterns, even though the group pressure they are feeling is implicit and indirect..

By asking group members to make these judgments personally, and recording them, I decrease the likelihood of such a “spontaneous” personal change in judgment. When I am really concerned about this dynamics happening in a particular group, I will even “collect” the individuals’ judgments before starting to build the group profile with the whole group. I do so by simply asking people to give me a copy of what they have recorded. I then ask them to refer to their copy as I record their personal results on the group profile. If individuals do verbally provide a different input on an item from what is recorded on their / my copy, I record what they say. I take these steps in order to decrease the likelihood of this happening, not force it not to happen.

- Although I may create a version group profile for my own insight[2] before I facilitate the “profiling” group session, I always build a group profile dynamically in real time with the group. By collecting, collating and recording the individual judgments in real time, in front of the entire group, I achieve the following.

- Each individual verbally expresses their personal decision in front of the other members of the group. Every group member experiences each person doing so. This creates an implicit sense of each person “owning” their judgments within the dynamic context of the whole group.

- Each member of the group sees the group profile being built. They can see the evolving patterns in the group profile. They can see where they are personally with reference to each of the other members of the group.

I am well aware that implicit “sub-grouping” around similarities can start to occur at this stage. But they do anyway in normal group discussion.

Underlying Psychological Dynamics

Recording individual judgments in a way that creates a publicly available group profile has many benefits for team and group development. It takes advantage of a number of well-known psychological dynamics.

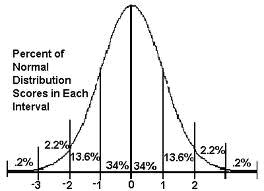

- Both the foreground and the background[3] of the group’s current decision-making are available to everyone in the group at the same time.

Each individual can see the patterns that exist in the group, whatever they might be – whatever degree of consensus or difference currently exists. At the same time, each individual can see where they stand with respect to the other members of the group.

- A tremendous amount of information about the underlying dynamics in the group moves from being “implicit, private” knowledge to “explicit, shared, public” knowledge. This allows the members of the group to focus more of their energy on the content under consideration, and less on figuring out where they stand with respect to the other members of the group on the issues.

Underlying Democratic Dynamics

Charting group patterns in this visual public manner reinforces the basic sense of democracy in the group.

- Each individual is shown to be an equally valued individual contributor in front of the whole group.

- The similarities and differences between the group members are also being made public. The degrees of similarity or difference are apparent to all.

This is the other side of democracy. Differences exist in democratic groups. Making this explicit allows individuals to deal openly with it. It removes much of the covertness that often exists in democratic situations. Sub-groups do form. Alliances are created.

The public group profile provides explicit insight into these possibilities. As individuals participating in a democratic process, each group member has a responsibility to deal with these similarities and differences. Making their personal stands public in a way that provides open insight into similarities and differences encourages people to do so.

The Benefits of the Psychological Disassociation

When I create a group profile in this fashion, I am actively working with the principle of “psychological disassociation”.[4]

- I take great care in making sure that each individual has an opportunity to make a personal record of the decision about the issue before I create the group profile. I ask them to record it. That’s extremely important. It allows individuals to experience the results of their internal decision making process, whatever it may be, from the outside in. The record of their decision making is step one in the disassociation process. They are moving from experiencing the process of making the decision to looking at a record of the result of that experience. That implicitly from them from a first position stance – experiencing – to a second position stance – looking at the results of their experience.

- I also create a public version of the group profile, in real time, in front of the entire group. That is step two in the disassociation process. The person’s decision about each option is no longer simply being “something which I have personally experienced inside myself, and then recorded to that I can see the results of my personal experience”. When the individual verbally declares each of their decision in front of the group, and I record it on the profile, they experience another level of disassociation. Their decision becomes “a decision that I have presented to others and seen publicly placed in the context of what others have done when they made the same personal decision.” The minute I record it, the individual experiences it from a third position, seeing it on the group profile. As result, individuals move from a “me” stance to a “my decision in the context of others’ decision” stance.[5]

The degree of psychological disassociation achieved by these actions reduces the likelihood that individual will engage in “flight – fight” personality dynamics when experiencing differences with other individuals in the group. Differences becomes “idea or issue” focused, not person to person focused. As a result, the possibilities for creativity within the group are deeply enhanced. The likelihood that the group will move to some level of eventual shared and creative consensus is increased. The possibility that the consensus when it occurs, is about new, creative possibilities that develop from the patterns of similarity and differences in the group is greatly enhanced.

Moving Beyond Simple Binary “Yes / No” Decisions

Starting with decisions that move beyond simple binary decisions is essential to all of this. The originators of Systematic Consensus use a scale to achieve this. I also used scales to achieve this. But based on work that I have done with Q-Sort methodologies in individual research, but I have also use option card ranking methods which I will describe later.

The technique chosen to move beyond simple binary stance must reflect

- the nature of the problem under consideration by the group,

- the time available for group work,

- and the skill / past experience / comfort level of the facilitator.

What is important is that the facilitator uses a technique that adds depth and nuance to the personal and group decision making process.

When working with problem solving groups, I often use these following steps. These steps become more and more difficult to manage as the size of the group starts to exceed small group limits (12 to 20 participants).[6]

- I introduce overall steps we will follow to the participants in an initial group meeting. This meeting usual follows some start up dialogue with a number of the members of the group to ensure that I understand their concerns and that I am the “right fit” person to be working with them.

- I meet with each person, in interview mode. I am trying to get a sense of each person perspective on the issues and options that the group is facing. I also start to build the rapport with each person which will make my involvement with them as a group a richer and more dynamically valuable experience.

- Based on these meetings, I organize / summarize my understanding in a set of issue / problem statements. The language that I use reflects what I have heard. I take great care to use their language, not my own.

- I circulate these statements to the group members as individuals for input and comment. I incorporate their responses into a final set of statements, and circulate them once more, asking if they are an accurate depiction of the issue or options that the group needs to address.

- I place the each statement on a card, often a simple 4” by 5” (or 4” by 8”) index card. I end up with a set of cards that define the issue or problem or options with which the group is dealing.

- I meet with each person and ask them to rank order these cards in a way that reflects their personal perception of importance or urgency or suitability. Again, the precise language I use in these instructions comes from the group’s context.

Card sorting moves individuals beyond the verbal. They engage fully – cognitively, emotionally and physically – in this process. As they sort the cards, they are paying attention to where they place in card in relation to all of the other cards – taking advantage of our human ability to consider foreground / background patterns at the same time.

Once they are through with the card sort, I ask them to verbalize their reasons for placing the cards in the way that they did. Essentially, this provides an opportunity for them to verbalize / rehearse things they might say later in the group. I record the results of their card sort, showing the individuals how they ranked the cards from “most to least”. This becomes their personal record.

- When the group reconvenes, I use some highly visual method to publicly record the results of each individual’s card sort into the group profile. Again, I make sure that they “verbalize” their input to me in front of the entire group.

Sometimes I do this as simply as possible, building a group profile, individual by individual, on flipchart or poster paper. At times, I get more technological, recording the individual’s input into a pre-prepared excel spreadsheet, using a computer and computer projector to project the process of building the profile on a wall or screen[7]. It depends on the group. Rapport is key. Using technology with a non-technology comfortable group is a problem, as is using paper based methods with a technology using group.

I am more likely to use 0 to 10 scales used in Systematic Consensus when I have to work with the group in a single session. I use a break out period to allow them to do the personal decision making. Using scales is easier to explain to a whole group in real time. They understand it, and need less personal direction than using card sorts. The time needed to “develop” the issues / options out of personal interaction is not needed.

Working Through Differences

Once the group profile has been built and is publicly apparent to everyone, the profile itself becomes a resource that I as the facilitator can use to encourage and to focus dialogue in the group. I can use it to explicitly move conflict from people to issues. I work with the group as follows.

- On the group profile, I visually identify two individuals who are “at opposite ends” on an item. I ask each person to talk to the whole group about the reasons they made the personal decisions they did. My verbal directions to each person indicate that I’m asking them to talk as a resource to the group, helping the group understand how and why they as a person came to the judgments that are apparent in the group profile.

- I create the opportunity for the other members of the people to ask the presenting individual questions. But I manage this to ensure that these are understanding questions, not personal statements in the form of questions that are really an indirect form of disagreement.

- Once both individuals have described their personal reasons, I turn to the group. I ask if, based on what each person has heard from these two individuals, does any member want to make a change in the judgments that is been recorded for them on the group profile.

If any individual does indicate a desire to do so, I first record the changes on the group profile in a way which is immediately apparent to the whole group. Then I ask the person who has made the change to tell the whole group their reasons for making this change. I facilitate this “change in judgment” process until no one indicates a desire to change their recorded judgment.

Clearly group dynamics, and interpersonal pressure, impact what is happening in the group during this activity. However, because each individual is changing a personal judgment which has been recorded in a disassociated fashion in a group profile, the change tends to be about the content of the ideas, not the implicit and explicit interpersonal alignments in the group. People usually provide content credible reasons for their changes.

Sometimes, the group members start to engage in discussions which lead to consideration of blended or new options that do not exist on the group profile. Often this creativity leads to clear and readily apparent consensus in the group.

What Happens Next

My experience indicates that the dialogue in the group at this point is a function of many different and interacting factors The length and intensity of this dialogue will depend on the issue, the history of the group, the nature of the individual personalities, the patterns in the group profile (large degree of similarity, bi-polar or tri-polar or … sub-groupings,) and the feelings that individual group members about the likely outcome.

But this dialogue now occurs in an environment which is deeply enriched by the amount of data about the group dynamic that is available to each individual. Groups seldom stay stuck; regardless of the difficulty of the issues they are dealing with, when this information is available to them. If consensus does not emerge from within the group, the new options can be clarified as a new place from which to recycle and start the individual judgment over again. “Stuck groups” often welcome this way of moving beyond their lack of progress.

What Happens to Individual Outliers

There is one other consequence of this type of group profile based consensus seeking that facilitators must be aware before they start using these processes. Individuals whose personal perspective on issues is dramatically different from the pattern that emerges during the group profiling are immediately identified in a public way as being different from most or all of the other members of the group. This individual must now deal with the consequences of being “distant” from the group in this way. This person can come to feel isolated, even blocked out from fruitfully participating in the groups’ further dialogue.

Sometimes such individuals simply treat this being related to the issues at hand, and continue their active participation in the life of the group or community. At other times, such persons feel alienated from the group.

People who end up with these feelings may do one of two things – withdraw from the life of the group or take a public stance of agreement with the group even when the person does not feel this. Facilitators need to be aware of this possibility, and when it occurs respond dynamically in a way that is respectful both to the individual, and to the whole group. These consensus seeking / facilitating techniques are not mechanical. They require facilitators to have deep skills, both as group process leaders and as sensitive human beings.

[1] Hedley is long retired, although some of his books on group process continue to help and to inspire folks who work with groups.

[2] Doing so often helps me decide on the exact format to use during the real time profiling session with the group. I tend to do it this “self step” if the timing and the dynamics of working with a particular group allow me to do so. If not, I develop the profiling format on-the-fly with the group.

[3] From Gestalt psychology, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Figure%E2%80%93ground_%28perception%29

[4] Severely disassociated personal states are considered sub-optimal by psychologists (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissociation_%28psychology%29). However, a level of disassociation from the immediacy of one’s feelings and judgments can allow an individual to be more productive in group situations. See Robert Kegan”s “In Over Our Heads” for insight into this type of disassociation. Google Robert Kegan for much more on these “mature adult processes” when participating in public/ social life.

[5] Robert Kegan’s classic 1994 book “In Over Our Heads” for more insight into the benefit of moving from 1st to 2nd and 3rd position, and the importance of this ability in our journey through life to mature adulthood.

[6] The modification of these facilitation techniques for large groups is beyond the scope of this article. But it can be done. Google “large group methods” to gain some insight into the richness possible.

[7] At one point in my facilitation career, I “decreased the time needed for this process” by preparing these profiles in advance of the group and simply distributing or projecting them to the group. I learned that the time I saved led to unanticipated consequence. Because each group member no longer went through the process of publicly providing their input to the profile, there was far less ownership of personal stances. The subsequent dialogue in the group was often far less rich and creative. I now resist the personal temptation, and often the urging of one or more group members, to do “save” this time. The process of publicly verbalizing personal decisions, and seeing them recorded as they are verbalized, is important to the dynamics among the group members.

xxx